Modern Corporate Governance vs. Decentralized Governance: Do Opposites Attract?

Stay up-to-date on trends shaping the future of governance.

Governance by code or by coding?

Sometimes, two forces which appear to be pulling in opposite directions may actually show some signs of convergence on closer examination; and the result can be more powerful than either force. The two forces I am thinking of here are modern corporate governance, the movement which started some thirty years ago to improve the governance of large companies; and decentralized governance, or DeGov, which in its manifestation in Decentralized Autonomous Organizations is barely eight years old.

The Rise of modern corporate governance, or mGov

Of course, corporate governance itself has a far longer history than the modern movement alone–right back to the limited liability legislation in the 19th century–but I am specifically interested here in the movement which started in the 1990s in several places to restore and refresh good practices in governance. Let’s call this movement ‘mGov’. mGov first manifested in a series of Governance Codes in the 1990s, starting with the Cadbury Code in the UK (1992) and the King Code I in South Africa (1994). These Codes were initially written to be guidance on good practices, but have since become legal requirements for listed entities and state-owned enterprises. Codes similar to these two pioneering ones have rippled around the world since then. The original versions have been refreshed too–King IV, the fourth incarnation of the King Code, was released in South Africa in 2016.

On top of the various codes have come extended reporting requirements which require disclosure of governance practices to levels not dreamed of thirty years ago. As an example, the WEF/ IBC Indicator set (available via here) lists four theme areas for governance in each of which detailed indicators are specified. And governance has of course been absorbed into the broader ESG movement to create greater accountability; and it is now scored, ranked and assessed as part of numerous ESG investment scorecards. The mGov movement has become a powerful force reshaping the corporate terrain for listed companies almost everywhere; by demonstration, it has affected even unlisted and smaller entities. Under the warcry of “comply or explain”, this movement has set standards for governing body composition, structure and processes which have largely converged internationally, even across differences in legal regimes.

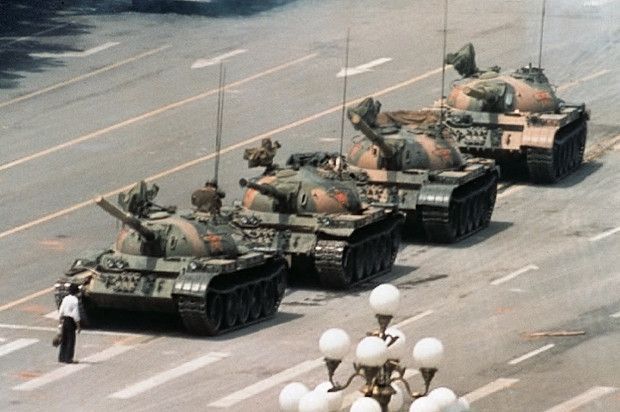

The tanker and the speedboat

Contrasting modern corporate governance with the fledgling decentralized governance movement is somewhat like comparing a supertanker with a speed boat in many ways–size and speed among them. There are many other clear differences.

DeGov is in part a reaction to the perceived and actual abuses in the centralized corporate realm, leading its proponents to want to construct digital spaces where cooperation could be fostered, rather than the destructive competition of late capitalism. The

Decentralized Autonomous Organization or DAO

is the umbrella term for the organizational manifestation of this movement. The term covers an increasingly wide range of entities, from internet-native ‘companies’ which have commercial intent and function even though they lack a legally enforceable form, to investment clubs and even affinity or social clubs of all forms and scales. My purpose in this article is not to add to the increasingly long list of reports on what a DAO is and how smart contracts built on crypto foundations function–if you want more background, rather read this very helpful description.

My purpose is rather to consider how the ‘speedboat’ and the ‘tanker’ may have more similarities in their trajectories than either would typically acknowledge.

The rise of DeGov

Over the past decade, the deGov movement has proliferated rapidly in the Web3.0 environment to the point where there are now thousands of DAOs with close to a million members according to some late 2021 estimates. The movement is led by ‘prophet-apostles’ like Vitalik Buterin, the creator and co-founder of Ethereum, the largest blockchain specifically engineered to host smart contracts. Smart contracts are nothing more than agreements encoded in ways which can only be changed through specific protocols–in extremis by imposing a ‘hard fork’ in which there is a permanent split in a blockchain.

To observers sitting in the ‘supertanker’ of mGov, the world of deGov looks like the cyber equivalent of the Wild West–with no sheriffs and lots of cattle rustlers. However, because the rules of DAOs are encoded in software making them deliberately hard or even impossible to change, the

deGov movement has in fact a strong focus on governance, at least during the setup of the DAO when the voting rules must be explicitly designed. This upfront focus has not made the deGov world immune from failure: there have been very public incidents of hacks, including of the very first DAO in 2016 from which $60m of investor money was stolen. As recently as December 2021, the Badger DAO reported a $130m hack. However, lest the observers on the supertanker become too smug about these failures of deGov, the rise of mGov has not prevented corporate governance failure either, even if it has probably reduced the incidence: it is all too easy to list more and bigger losses accruing as a result of governance failures even in the era of mGov (remember Enron in the US? Wirecard in Germany? Steinhoff in South Africa?)

Representative democracy vs Athenian democracy

So, on the surface, we see a tanker (mGov) and a speedboat (deGov). We see governance by code (mGov) and governance by coding (deGov). We also see that mGov is founded on the notion of ‘representative democracy’ where shareholders elect directors to govern and largely leave them to do their job unless and until they fire them; while deGov is akin to Athenian democracy, where members vote directly on all defined issues of common interest, using a variety of protocols.

So far, so different. But look closer at deGov and you start to see signs of convergence

in some respects.

Four signs of convergence in DeGov

First, legal structures are evolving to bring DAOs in from the cold of cyberspace where members have no legal protection from liability or the ability to enforce rights against other entities. In 2021, Wyoming became the first US state to incorporate provisions for DAOs into its LLC law, allowing DAOs to receive legal recognition. Malta in the EU already offers legal status for DAOs. Not all DAOs will want or need legal persona, but once they have it, the speedboat will at least be subject to the same laws of the high seas as the tanker

Second, just as services rating and ranking corporate governance have proliferated under mGov, we can see the

beginning of similar services seeking to bring transparency to deGov. As one example, Boardroom started up in 2020 offering an API so that DAOs can connect to offer standardized governance interface for reporting to their members. Boardroom’s leaderboard ranks DAOs according to metrics of activity, engagement and participation: for example, the number of proposals submitted to members, the number of participants and the number of ballots cast for proposal. The Boardroom directory currently lists 81 DAOs and it is possible to view specific proposals, voters’ public keys and the treasury balances for each. Services like this are

small steps towards greater consistent transparency in the deGov world; after all, this is what accounting and disclosure standards seek to do in the mGov world.

Third, the governance of the larger DAO ecosystems is evolving by creating layers of more representative governance to enable more effective decision-making than community votes on every topic. Take Gitcoin as an example. Gitcoin is a community which claims 312,000 monthly active developers engaged on a range of Web3.0 projects writing open-source code and protocols to ‘create the digital public infrastructure of tomorrow’. Gitcoin became a DAO in 2021 and has adopted the concept of ‘stewards’ in its governance. Stewards are selected from and by community members because of their commitment to Gitcoin’s mission and their willingness to get involved. Members may delegate their votes to stewards. Doesn’t that sound like a combination of a proxy service and volunteer director in the mGov world?

Finally, the man whom I have described above as

the prophet-apostle of the deGov movement, Vitalik Buterin, has himself weighed in on the emerging weaknesses of pure deGov

coin-based voting in 2021. In this lengthy but fascinating article, he diagnoses the problems with it, and suggests a range of possible solutions. These include introducing skin the game where DAO members can be held liable for the costs of their actions on other members; and forms of non-coin driven governance such as ‘proof of personhood’–a Web3.0 term for applying rules like ‘one person one vote’ which are of course common in voting in cooperative associations. Many of these sound like solutions available in different mGov settings today.

Early signs of convergence from mGov

These signs of change in deGov suggest that it is the speedboat which needs to change; and indeed, that it is changing to become more like the tanker, albeit in a semi-chaotic way characteristic of early-stage sectors. What evidence is there that the tanker also is changing?

The evidence for this is harder to see yet–tankers take a long time to turn–and therefore my hypothesis is more speculative. First, let’s recognize that

modern capitalism is a long way away from being a democracy of individual shareholders. In an era when most stockholdings are held not by individuals but by funds, most voting happens passively, via intermediaries like proxy services. In a 2019 Stanford Law paper, Ross Buckley and his colleagues Federico Panisi and Doug Arner have already proposed how the use of blockchain for voting in public companies has the potential to make shareholder democracy more direct, transparent and effective. Greater activism by civil society may push trends faster.

Second, I think that the emphasis on ‘stakeholderism’ in the latest version of mGov will lead the ‘tanker’ to turn in time towards introducing more decentralized elements of governance. Recognizing multiple stakeholders beyond shareholders inevitably adds governance complexity. The mGov situation today is arguably akin to when qualified franchises in early democracies allowed only one category of society such as landowners to vote for representatives. Broadening the franchise took decades of protest and struggle in many places. Traditional models of shareholder-based representative democracy will likely also struggle to incorporate wider expectations in a reasonably transparent way without conflict and turbulence. However, DAO-type structures may offer corporations safe digital spaces in which to engage with specified stakeholder groups such as customers or suppliers. Corporate DAOs could include reward systems via tokens which incentivize engaged consumers or suppliers and invite them to express views on relevant issues through voting. This could be complementary to shareholder elected representation. But it may make corporations slightly more like consumer or producer cooperatives over time, responsive to and influenced by the needs of these groups.

Towards synthesis

With respect to mGov and deGov, we are still a long way from a synthesis stage which inevitably follows the current antithesis stage in Hegel’s model of progress. But my argument is that already, the

antithesis of the mGov and deGov movements may be less pronounced than it appears. And the combination of the strengths of each could be powerful indeed for better digital governance in the economy of the future.

At Integral, we provide ESG Consulting advice, evaluation, facilitation, mentoring and coaching services to develop governance systems that fit your organization’s purpose and stage of growth. To explore further how we can help you,

read about our services, or

set up a free consultation.

S H A R E